Your cart is currently empty!

5. Below Van Cortlandt Ave South Bridge

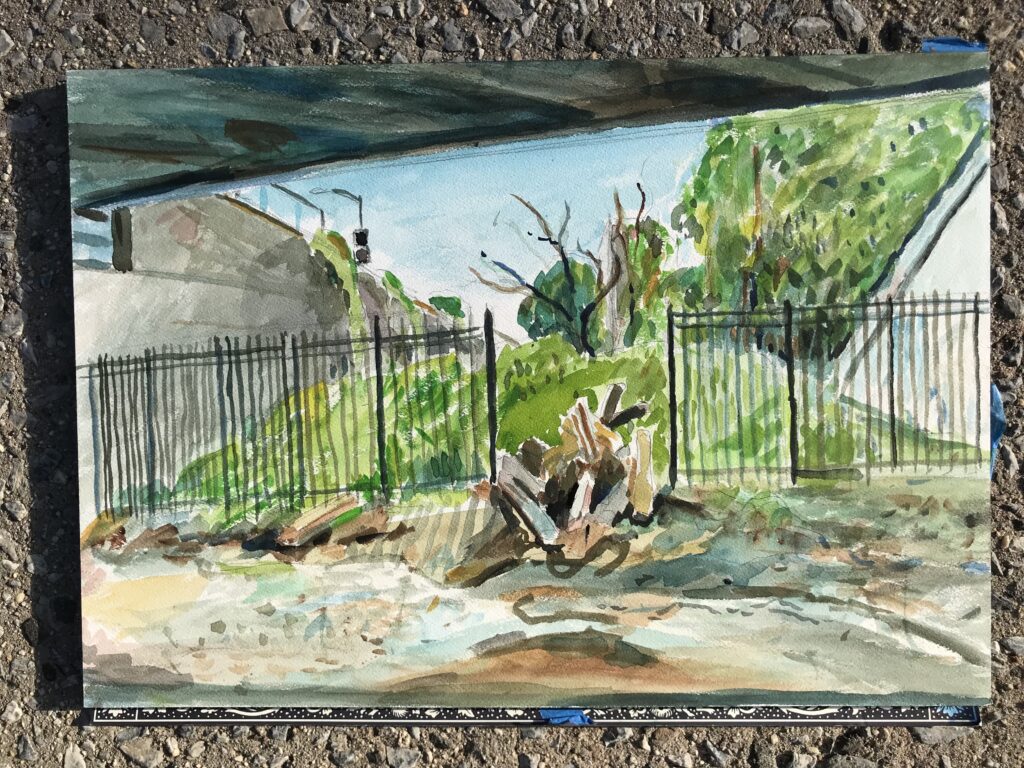

In this session, I found myself back at the Van Cortlandt Park South bridge. Yet, unlike before, my vantage point shifted beneath the bridge, immersing me in the pathway carved by IDA’s raging flood waters – the future route of the Daylighted Tibbetts Brook.

I’m painting a landscape that is technically fenced off.

But there are a few spots where you can access it if you really wanted to. I felt the need to get into the path of the water itself, not to observe from the side banks.

There is an unofficial path leading through bushes behind a storage container into this man-made valley—once called the Putnam railroad, or “The Old Put.”

Part of my grandfather’s commute to West 4th in Manhattan was along this line. He died 3 years before I was born.

My uncle took this railroad from Yonkers to attend Manhattan College as a student. He married my aunt sometime in the 60s at the now boarded up Parish Hall a stone’s throw away across the street.

I didn’t know any of this before I moved here in 2020. 60 years later, I’m right down the block under a bridge with the other holy water.

Reflecting on it now, I realize these landscapes subtly shaped my youth, their influence quietly woven into my past.

To know that my grandfather most surely uttered the words “The Old Put,” forms new vibrant connections.

This embankment is steep and scattered with litter. There are puddles at the bottom framed by burnt umber colored terrain that paints my shoes and pant cuffs. There are tall wrought iron gate at both edges of the bridge with a NYC parks logo on top. I think they are kind of new.

The gate is open, so I go under the bridge.

“Is this safe?”

The graffiti artwork all across both walls assured me. Many people paint here, unbothered enough to create elaborate works—I am not the first.

I was slightly concerned by the dozens of neon orange bridge inspector markings on the ceiling, calling attention to cracks of various shapes and sizes. I looked around for evidence of the ceiling falling and didn’t see much, so I took my chances.

The ground under the bridge had a few rail ties, sporadic puddles, and plenty of wet mud with millions of raccoon paw prints and no obvious human tracks whatsoever.

Pigeons occupied the spaces up above, rather vocally. Was I disturbing them?

There was a segment of unattached chain link fence standing up in the middle of the underpass, with dried muddy decaying leaves caught in the wiring all the way up to the top. A month ago, a deep river moved through here for about a day, with currents fast enough to be dangerous. The fence was a clear sign that the water had been well above my head.

On the other side of the opposite fence, there is an explosion of vegetative greens as the rail right of way opens out into sunlight, impassible to the casual explorer, with large bodies of standing water, patches of light yellow green duckweed and thick stands of blue-green phragmites. Those plants seem to be doing rather well, with no hesitations about embracing the aquatic expressions of this land.

The door on this gate is blocked with a pile of muddy wooden railroad ties.

At first I thought humans piled the wood there to discourage trespassers, but I wonder if it was the flood water?

I tried lifting one. It was quite heavy

I wanted to paint this threshold between Van Cortlandt Park and what we hope becomes a new public park. I imagine this passage under the bridge from dark to light might be quite dramatic if handled well. There is staging capacity here, this moment before it opens up into the expansive skies adjacent to Major Deegan. Will this space still read as a boundary? It is a marsh boundary in old maps.

Geographic boundaries for water are watersheds. Municipal boundaries don’t follow that same logic.

The bridge, the park, the rail line, all fall under different agencies and overlap in this location. Will Van Cortlandt Park annex this rail corridor? Or will a new organization emerge? Humans complicate. Water flows.

There is a rail trail on the northern border of Van Cortlandt Park along this rail line. NYC Parks clears the snow in the winter, and Westchester county does not. There is a sharp line at the border with frustrated cross country skiers and/ or walkers.

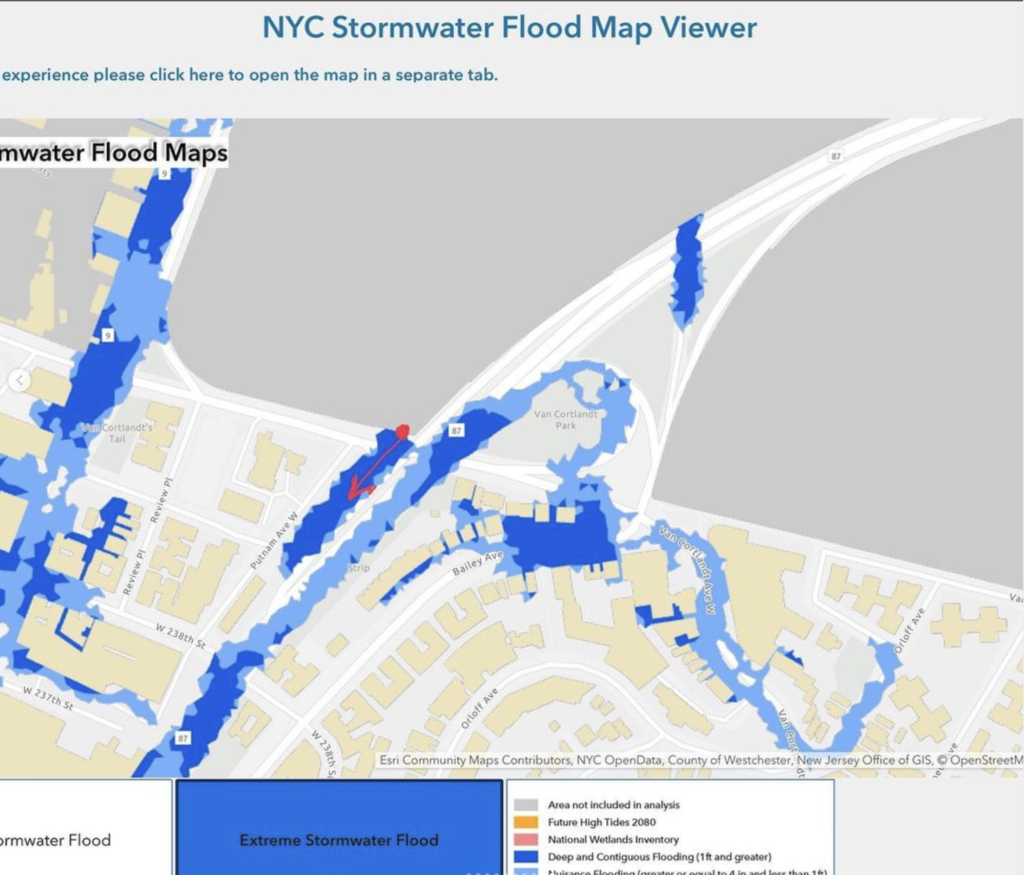

This area is marked on the May 2021 NYC Stormwater analysis maps as having significant “deep and contiguous flooding of 1 foot or greater” during any rainfall where 3.5 inches of rain falls in 1 hour. In august we broke the record for 1 hour rainfall, measured in Central park at 1.91 inches in 1 hour Two weeks later we broke the record again. This time 3.15 inches in 1 hour.

One inch of rain falling on 1 acre of land weighs about 113 tons, approximately the weight of a 1 story house, or the Anish Kapoor “Bean” public sculpture in Chicago. Boom.

The May 2021 map states this extreme rainfall event is considered a 100 year storm, with a 1% chance of happening any given year. How many of those will we have by 2080, when some aggressive sea level rise predictions are as high as 4 feet?

The painting session was quiet and reflective. Besides the pigeons, I was visited by a yellow jacket and several birds out in the marshland. I suspect the raccoons may have been watching.

There was very little vegetation under the bridge, a few puddles speckled with Seurat-like dots of duckweed contrasted against swirls of red iron oxide, mimicking the fluid gestures and saturated colors of the graffiti on the walls, mimicking the wind of the pigeons.

My hope is that this space maintains its artistic character, its unique blend of urban and natural elements, even as the stream is reintegrated into the landscape.

I noticed a pile of human feces as I climbed up the embankment; the noises of the busy city becoming present again.